Unrealistic Assumptions Give Rhodium Analysis Overly Rosy Outcomes

Quickly reading through the Rhodium Group’s latest May 2024 report on the future of carbon capture and storage (CCS), you could be forgiven for thinking that CCS may yet be able to play a role in decarbonizing US heavy industry. But you’d be wrong. Perhaps not immediately obvious to the casual reader, the report’s predictions depend on unrealistic assumptions of sustained, sky-high oil prices, negligible costs to produce a barrel of oil, and implicitly optimistic estimates for CCS costs.

In reality, CCS is only consistently profitable when CCS is coupled with natural gas processing facilities to increase oil recovery from existing petroleum reservoirs. Natural gas processing with CCS for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) is a process in which ancient, previously stored carbon dioxide (CO2) is piped to the surface with other gasses. Some ancient CO2 is vented directly to the atmosphere; the rest is reinjected in aging oil reservoirs to flush out more oil. Not least because each ton of injected CO2 (tCO2) increases petroleum extraction by about three barrels of oil, CCS-EOR for any industry–but especially natural gas processing–is net carbon positive. The result: the only CCS implementation that makes business sense is the version of CCS that most damages the environment.

Given that, why does the Rhodium Group project substantial adoption of CCS across heavy industries? We’ve done the legwork. Allow us to explain.

After noticing that all three of Rhodium’s scenarios were based on several unrealistic and/or unspecified assumptions, we decided to stress test their results. Although Rhodium neither makes its model publicly available nor fully specifies key assumptions and input data, they do provide enough description of their approach such that a reasonable approximation can be assembled.

Following Rhodium’s cash-flow-based approach, we built a discounted cash flow model to estimate the net present value (NPV) of CCS retrofits for eight heavy industries. Our cash-flow model simulates project profitability in units of NPV per tCO2 injected ($/tCO2). We gleaned information from Rhodium’s cited sources to characterize the ranges of CCS costs, and we employed Rhodium’s stated financial and macroeconomic assumptions (e.g., inflation rate, discount rate). Rhodium uses an unspecified ‘installation capacity’ constraint to spread CCS facility construction through time. We dispensed with imposed time variation and simply qualitatively compared our simulated project NPV $/tCO2 with Rhodium’s projected total installed capacity in 2040.

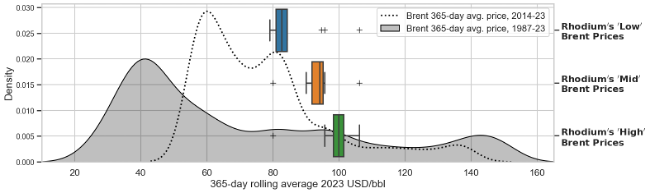

After confirming our forecasts align with Rhodium’s under three cases mimicking Rhodium’s ‘Low’, ‘Mid’, and ‘High’ Emissions scenarios, we took our model for a spin using a broad range of inputs that better characterize likely future scenarios. For each heavy industry, we simulated 2000 different cases. Each used a random sample of input data drawn from realistic, historically informed distributions of CCS costs, oil prices, and oil break-even prices. We built those distributions using updated CCS costs, daily Brent price data (Fig. 1a), and oil-breakeven prices specified by oil-industry executives. We used a realistic oil-recovery factor of 3 bbl/tCO2 when estimating profits from CCS-EOR. Figure 2 below summarizes what we found. A detailed report is forthcoming. In the meantime, code is described and linked here.

What did we find? CCS with geologic storage is never profitable for any industry (Fig. 2). Don’t mistake the foregoing statement as justification for increasing subsidies. We found that CCS with geologic storage doesn’t become consistently profitable for hydrogen plants until tax credits exceed $200/tCO2; petroleum refining requires ~$300/tCO2. For well below those amounts, there exist substantially more effective, proven targets for federal government support that will spur decarbonization (e.g., rooftop solar panels, improving grid transmission infrastructure, streamlining permitting for offshore wind, etc.). Such investments provide the added benefit of grid modernization and direct community investment, and it perhaps goes without saying that when we transition away from fossil fuels, there will be little need to decarbonize natural gas processing, petroleum refining, or ethylene cracking. In the case of the cement and steel industries, multiple promising new petroleum-free technologies for decarbonization are in advanced stages of development.

Patterns of existing CCS infrastructure in the US are consistent with our finding that only CCS-EOR is ever profitable and that it is only consistently profitable for the natural-gas processing industry. With the exception of a limited number of exhibition projects, all CCS facilities in operation today are used for EOR, and the lion’s share of that capacity is connected to natural-gas processing.

So why does Rhodium forecast substantial uptake of CCS? First, none of their cases are among likely future scenarios. In particular, their ‘Low Emissions’ case combines sustained very high oil prices (Figure 1b) and what are likely unrealistically low CCS costs for implementation. Even their ‘High Emissions’ case assumes oil prices will stay well above the median price of Brent crude. Furthermore, after trial and error, we infer that the price Rhodium assumed for oil breakeven is also unrealistically low. Finally, although their written conclusions do not distinguish between CCS with geologic storage and CCS with EOR, they seem only to look at CCS-EOR, which is the only type of CCS that has any chance of being profitable.

In short, Rhodium’s projections are unrealistically rosy because all three of their cases fall into the small collection of unlikely situations in which CCS-EOR is profitable.

Figure 1a. Historical Brent crude prices, adjusted to 2023 dollars

Time series of the daily Brent crude price ($/bbl) since May 1987, with each day’s closing price adjusted using the yearly Consumer Price Index to 2023 USD (red line); and (2) the 365-day rolling window average daily Brent price (blue line).

Figure 1b. Rhodium’s three oil-price cases compared to the true distribution of 365-day rolling-average Brent crude prices

Rhodium’s three Brent-price scenarios (blue, orange, and green distributions) in the context of the 365-day rolling average Brent price (gray shaded) and an alternative distribution (dashed line) including only data since Jan 1, 2014.

Figure 2. Project profitability of CCS retrofits for US heavy industry

The left panel shows ranges of project profitability for CCS with geologic storage, which receives government subsidies of $85/tCO2; the right shows the same for CCS with enhanced oil recovery (EOR), which receives subsidies of $60/tCO2. The distribution for each industry is made up of 2000 simulations of net present value per tCO2 injected, using random samples drawn from realistic distributions of oil breakeven price, oil price curves, and CCS costs for the industry. Consistent with current regulation, we allowed credits to increase with inflation starting in 2027.